With the advent of the post-colonial era a few daring creative filmmakers emerged from the teardrop shaped island named Sri Lanka, nestled under India in the Indian ocean. Their fire was ignited in the early 1900s when silent films from Europe were screened for the first time via an acquired projector from abroad. In the early 1930s there was a massive influx of Indian films that was screened in newly built network of cinemas. In the 1930’s and 1940’s with the emergence of spoken films the West started to dominate the global interest. With the advancement of technology, the aspiring filmmakers of Sri Lanka finally got the opportunity to create history in 1947, producing the first locally produced Sinhalese film Kadawunu Poronduwa (Broken Promise).

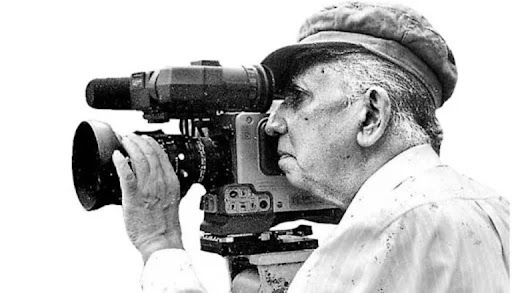

It’s hard to imagine Sri Lankan film without the talented filmmaker Lester James Peries. He specialised in film direction, screenwriting and film producing. He is considered by many the father of Sri lankan cinema. In a career spanning almost 60 years he has contributed immensely to the development of film in Sri Lanka. His movie Wekande Walauwa, starring Ravindra Randeniya and Malini Fonseka, was Sri Lanka’s first ever submission for the Academy Awards and the film Nidhanaya was included among the top 100 films of the century by the Cinémathèque Française. His first film was Rekava (1956), a documentary-style film based on an original story and featuring a predominately inexperienced cast was a great success and garnered international acclaim after being screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

But it was his next film Gamperaliya (1963) that opened up a new world of filmmaking within Sri Lankan cinema. it was adapted from the novel Gamperaliya by Martin Wickramasinghe. The film was ground-breaking in Sinhala cinema shot entirely outside of a studio using one lamp and hand held lights for lighting. The movie portrayed a rural Sri Lankan village setting exemplifying inner family tensions to symbolize wider social issues. The film was internationally acclaimed as it won the Best Director and Best Film awards at the 1965 Sarasaviya Film Festival. It was entered into the 3rd Moscow International Film Festival. It was shown in Cannes Film festival in May 2008 under the French title Changement au village under section ‘Restored Classics’. Subsequently it went out on general release in French cinemas. In 2001, the film was identified as a world heritage by Cinema Thek Institute in France. Peries’ Nidhanaya (1970) demonstrated his continuing development and success as a director and also presented masterful performances from Gamini and Malini Fonseka in the lead roles of Willy and Irene.

The Sri Lankan State Film Corporation was established in 1971 to further encouraging original screen writing from local filmmakers. Another masterpiece of artistic filmmaking came when Dharmasena Pathiraja released Bambaru Avith (The Wasps Are Here) in 1978. The film focuses on a small fishing village and tells a story of disruption, exploitation and loss caused by the arrival of capitalism.

The popularity of television and the beginning of the Sri Lankan Civil War between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, also meant that cinema-goers were more inclined to stay at home. Peries’ Baddegama (1980), Kaliyugaya (1982), and Yuganthaya (1983), all of which continued his successful fusing of artistic techniques with depictions of conflicted characters and family life in rural Sri Lanka. It wasn’t until 1996, when Prasanna Vithanage released his second critically acclaimed film, Anantha Rathriya, that a new filmmaker of note was recognised. He became one of the most important Sri Lankan filmmakers since Peries, going on to release both Purahanda Kaluwara (Darkness on a Full Moon Day) and Pawuru Wallalu (Walls Within) in 1997 to further critical acclaim.

Vimukthi Jayasundara has released a string of successful films, including Sulanga Enu Pinisa (The Forsaken Land) (2005), and Ahasin Wetei (Between Two Worlds) (2009), the former of which won the coveted Camera d’Or at the 2005 Cannes Film Festival. Not only have these films played well to audiences and critics and won awards from the world’s major film festivals, but they have also tackled grittier subjects, such as social transformation, abortion, and the results of the Civil War on both families and soldiers. They also, particularly with regards to Jayasundara’s work, continue to push the boundaries of narrative, form and Sri Lankan storytelling, so although audience figures continue to decline and cinemas continue to close, the enduring presence of daring and original filmmakers prevent Sri Lankan cinema’s future from looking entirely desolate.